Overview | Clinical Scenarios | References

By Jacqueline Landess, MD, JD

OVERVIEW

Definition

Correctional psychiatry refers to the delivery of psychiatric care within correctional settings, such as jails, prisons, and may include community settings (including working with patients on probation or parole). There is a high need for quality, timely, and competent care for patients in these settings.

Psychiatrists tend to see more acute crises in jails than prisons.

Frequent examples include:

- Acute suicidality and suicide attempts

- Untreated psychosis and mania

- Substance intoxication and withdrawal

In prisons, caseloads tend to be more stable over time and psychiatrists often see patients on an “outpatient” basis, though some prisons also have psychiatric hospital-type settings within the prison. In both jails and prisons, there are more patients with personality disorders, intellectual disabilities, and substance use disorders, as compared to the general population.

Other Definitions

| Terms | Lock-ups | Jails | Prisons |

| Operated by | City or small precinct | County or City | State or federal government |

| Length of stay | Very short term-days to weeks | Months to years | Years, up to life sentence |

| Other | Most (85%) inmates are awaiting trial. Some serve time for misdemeanor cases (< 1 years). | Inmates are post- conviction |

General Principles

There are many misconceptions about correctional psychiatry. Including1:

- Incarcerated patients are less deserving of mental health care than other patients.

- Working in correctional psychiatry supports mass incarceration.

- Correctional psychiatry is more dangerous than practicing psychiatry elsewhere.

- Correctional psychiatry is a less respectable subspecialty.

Read more about these misconceptions and perspectives about working in corrections here. Correctional work presents unique challenges, but also rewards.2 There are high numbers of individuals with serious mental illness (SMI),3 such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in correctional systems, particularly in jails; approximately 15% of men in jails have SMI and 30% of women.4 75-85% of incarcerated persons have a substance use disorder. One study found that 15% of former prisoner deaths were attributable to opioid overdose.5 Thus, there is an urgent need for psychiatrists and mental health professionals to deliver quality care in these settings.

Background

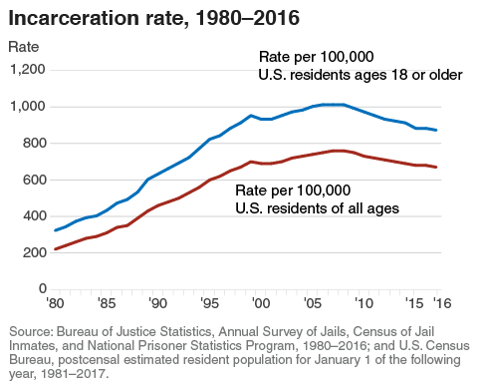

The correctional population has greatly increased since the 1970s. There are currently over 6 million people who are either incarcerated, on probation, or parole. This equates to 1:40 US citizens under correctional supervision.

Subsequently, the number of inmates with serious psychiatric illness and substance use disorders has also peaked. Different factors have led to this mass incarceration effect:

Right to Treatment

People who are incarcerated have a constitutional right to medical and psychiatric treatment. Correctional systems who do not provide adequate care may be found liable under both malpractice law and/or civil rights laws.7 Read more about inadequate discharge planning and the “dumping” of detainees here. (p. 11)

CLINICAL SCENARIOS

Scenario #1: You see a patient who was booked into jail. He states that he missed his long acting injection for aripiprazole and is showing signs of psychosis. What medication do you suggest or initiate?

- Be aware of the jail’s formulary.

- Read about tips for prescribing in corrections.8

- Certain medications are not prescribed in jail due to cost, risk of diversion and/or abuse.

- The jail (usually the county) pays directly for medications. They cannot bill Medicaid or Medicare with few exceptions.

- A patient may have non-formulary medication stopped when incarcerated. Here’s an example.

- In this case, if long acting aripiprazole is not on the jail formulary, the patient could be given oral aripiprazole, since this is generic and likely on formulary. However, if the patient has a history of non-adherence, he should be carefully monitored to ensure he does not begin refusing while at the jail.

- If he refuses medication except for LAI, you could initiate an appeal or pre-authorization request for the jail to cover the LAI.

- Adequate discharge planning should occur to ensure he can resume the LAI once he leaves.

Medications that may not be available in jail due to cost:

- Paliperidone Long Acting Injectable (LAI)

- Aripiprazole LAI

- Naltrexone Long Acting Injection

- Medications that are not yet generic: vortioxetine, vilazodone, valbenazine, brexpiprazole, cariprazine and others

Scenario #2: You see a patient who is incarcerated. His chief complaint is insomnia. He tells you the only medication which has worked for him is quetiapine. What do you do?

- Insomnia is one of the most common complaints in correctional environments.

- Diagnose the insomnia disorder, if present, and evaluate for comorbidities such as adjustment disorder

- Sleep hygiene is first line for primary insomnia but may also try agents such as mirtazapine, hydroxyzine or short term Benadryl

- Other agents such as trazodone or quetiapine may not be available due to formulary restrictions

- Certain medications are not on formulary at jails or prisons due to a higher risk of abuse or diversion in these environments. Examples:

| Quetiapine | Trihexyphenidyl |

| Trazodone | Narcotics |

| Bupropion | Psychostimulants |

| Gabapentin | Benzodiazepines |

Scenario #3: You are treating a patient with schizophrenia with medication for 6 months. He obtains bond and is released without follow up or medication. He returns the next day asking for a prescription. What do you do?

- Individual jails have policies about how much medication a patient may receive upon release.

- However, he should at least be provided with a script for a reasonable amount of medication (typically, at least 30 days) until he can find an outpatient prescriber.

- Good faith efforts should be made to link him with community treatment providers.

- Jails should provide liaisons or case managers to assist in discharge planning.

- If a jail does not provide a patient with medications or follow up upon release, they could be violating the patient’s constitutional rights and be liable if the patient decompensates.

Scenario #4: You see a patient who reports that he sees “clowns” and hears “dead presidents whispering” to him. He states these symptoms are constant and have been ongoing since he was 10. He shows no objective signs of psychosis on exam. He states that gabapentin, psychostimulants and benzodiazepines have worked best for his symptoms.

- Consider malingering. Individuals in a correctional setting may have incentives to malinger psychiatric symptoms. Incentives include a desire to obtain medications to divert or abuse, desire to absolve themselves of guilt or obtain a reduced sentence by pleading NGI or other mitigating defenses.

- The psychiatrist should be aware of these potential motives and consider exaggeration or falsification of symptoms, especially when atypical symptoms are reported.

- Be aware that some patients engage in adaptive malingering. They may falsely report symptoms in order to obtain expedited psychiatric care. For example, a patient may falsely report SI upon entry into the jail in order to see a psychiatrist sooner and have their medications continued, knowing that otherwise they might wait weeks to have their medications continued.

- Malingering is an opinion reached after all other psychiatric diagnoses are considered and excluded. Consider wording such as “suspicion for feigning or exaggerating” and document why, rather than stating “Patient is malingering.”

Scenario #5: You see a 25-year-old patient who has been incarcerated for 3 days. This is her first incarceration. She has no clear psychiatric history but states she wants to die and will do it “however I can.” She is withdrawing from several substances. What are your next steps?

- Any mention of suicide should be taken seriously

- Suicide is the leading cause of death in jails

- The most common method is by hanging

- Jails have a higher suicide rate than prisons

- Factors leading to suicide include:

- Shock of confinement,

- Isolation from family,

- Substance withdrawal,

- Loss of reputation, job and other social connections,

- Worsening underlying psychiatric symptoms,

- Inability to access mental health

- Read up on tips for assessment.

- Use evidence based tools for screening, such as the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale

- Treat according to suicide risk

- Suicide watch in jails

- Highest risk inmates usually placed in specialized pod

- More frequent checks by officers and MH staff

- Often has expedited referral to psychiatry/prescriber

- May be on camera monitoring in his/her cell

- Often given canvas gown and blanket for means restriction

- Treat underlying dynamic risk factors

- Substance withdrawal

- Psychosis

- Adjustment issues/agitation

- Isolation

- Depression

- Connection to support/MH treatment

- Develop a longer term safety/treatment plan

REFERENCES

- Morris NP, West SG. Misconceptions About Working in Correctional Psychiatry. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2020 Jun;48(2):251-258.

- Simpson J. Correctional Psychiatry: Challenges and Rewards. Psychiatric Times. 2014; 31(2). Available from: https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/correctional-psychiatry-challenges-and-rewards

- James D, Glaze L. The Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates. Bureau of Justice Statistics Report. 2006; Available from: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mhppji.pdf

- Steadman HJ, Osher FC, Robbins PC, Case B, Samuels S Prevalence of Serious Mental Illness Among Jail Inmates. Psychiatric Services. 2009; 60(6):761-765.

Maruschak LM, Minton TD. Correctional populations in the United States, 2017-2018. U.S. Department of Justice. Available from: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpus1718.pdf - Binswanger, I. A., Blatchford, P. J., Mueller, S. R., & Stern, M. F. (2013). Mortality after prison release: Opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Annals of Internal Medicine, 159(9), 592-600.

- Estelle v Gamble, 429 U.S. 97 (1976).

- Pietrzak M, VanDercar A, Landess J, Hatters Friedman S. Charles v. Orange County: A Constitutional Claim for the Discharge and “Dumping” of Mentally Ill Detainees. AAPL Newsletter. Spring 2020. Available from: https://www.aapl.org/docs/newsletter/AAPL_Spring_2020_Newsletter.pdf

- AAPL Practice Resource for Prescribing in Corrections. June 2018; 46(2 Supplement) S2-S50. Available from: http://jaapl.org/content/46/2_Supplement/S2

ADDITIONAL READING

- Trestman RL, Appelbaum KL, Metzner JL. Oxford Textbook of Correctional Psychiatry. NewYork, NY: Oxford University Press; 2015.