Overview | Clinical Scenarios | Additional Tips | References

By Monika Pietrzak,MD, JD and Jacqueline Landess, MD, JD

OVERVIEW

General Principles

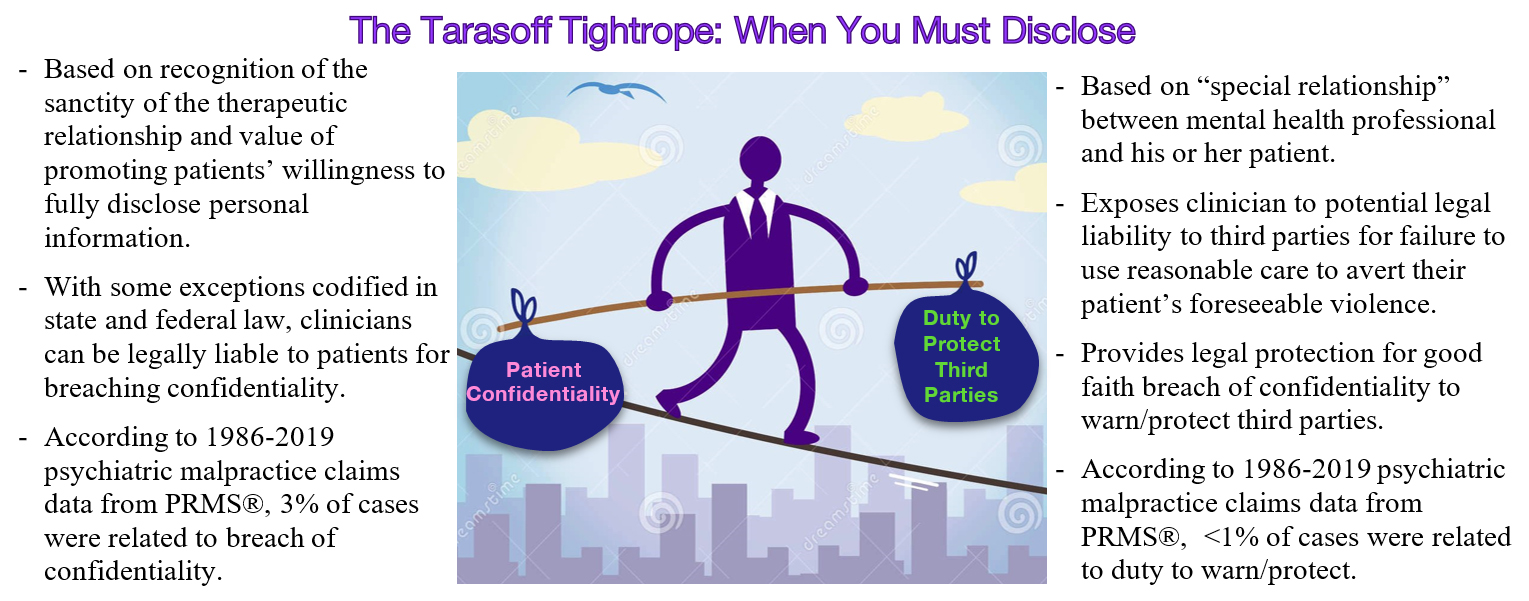

- Mental health professionals have a duty to keep their patients’ mental health information confidential. However, when a patient poses a danger to others, mental health professionals may have a legal duty to also take steps to protect potential victims of the patient’s violence.

- The duty to warn or protect third parties of their patient’s potential violence arises from the landmark California Supreme Court case of Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California and is commonly referred to as a “Tarasoff duty.”

- The Tarasoff court eventually redefined the imposed duty of mental health professionals to protect (rather than warn) third parties from potential patient violence, which perpetuated enduring confusion surrounding the distinction between these terms.

- Duty to warn: obligation to notify endangered third parties about the risk of violence.

- Duty to protect: obligation to take one or more steps to protect endangered third parties from harm – various options include, but are not limited to, warning potential victim and/or police, hospitalizing patient, or increasing frequency of office visits.

- The Tarasoff case and its progeny generated a firestorm of controversy over the therapeutic implications of limiting patient-therapist confidentiality. However, ensuring research found that the anticipated chilling effects of Tarasoff warnings have not materialized in clinical practice. For instance, see here and here.

- An overview of the historical evolution of post-Tarasoff regulations in other jurisdictions can be found here.

- A clinician must weigh the patient’s right to confidentiality with their legal, ethical, and clinical duties to protect potential victims of their patient’s violence.

- The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act [HIPAA] Privacy Rule permits disclosure of a patient’s protected health information in order to lessen a serious and imminent threat to the health or safety of third parties. The provider must have a good faith belief that disclosure is necessary, and the disclosure must be consistent with applicable state laws and ethical standards.

Jurisdictional Considerations

Nearly all states have statutes or common law that permit or require mental health professionals to disclose confidential information about potentially violent patients who pose a danger to third-party victims. The specific requirements of these laws vary by state.

Below are examples of state law variations in duty to warn/protect regulations. See here for additional info.

- Although most jurisdictions limit the duty to explicit threats made by a patient to the mental health professional, some states also recognize threats communicated by third parties (such as family members) or inferred from a patient’s actions (such as escalating agitation with previous history of association with violence).

- Mental health professionals’ legal responsibility to third parties is predicated on foreseeability of harm. However, different jurisdictions have interpreted the scope of foreseeable victims in a variety of ways. While most states have narrowly applied the duty to protect readily identifiable victims, others have extended the duty to unidentified individuals who may be foreseeably endangered by a patient (even if no specific target was identified by the patient). This may include threats to property or the general public at large.

- SMI Adviser, an APA and SAMHSA initiative, outlined each state’s Tarasoff laws as of February 18, 2020. Look up your state law here.

CLINICAL SCENARIOS

Scenario #1: A 30-year-old man with a history of schizoaffective disorder sees you in clinic to resume psychiatric treatment after several months of medication non-adherence. He reports non-command auditory hallucinations, paranoia that he is being monitored by the government, and is drinking alcohol daily. He indicates that he keeps a loaded gun in his basement for self-protection and would use violence to defend himself if anyone tried to attack him, but he does not identify feeling threatened by specific individuals and never gives any other indication that he wants to harm anyone.

- You should complete a thorough violence risk assessment. There is probably inadequate information to know, at this point, whether this patient presents a serious danger of violence to others. Although he did not make any explicit threats, he is psychotic, paranoid, using alcohol, and has ready access to a lethal weapon.

- Consider general risk factors associated with increased risk of violence, patient characteristics associated with increased risk of engaging in violence after a threat, and where a patient is on the pathway toward violent action. These may include the following:

- Seek multiple sources of collateral information, including past medical records and reports from close contacts, such as partners, family members, and friends.

- If you believe this patient is at increased risk for violence, then develop a treatment plan which addresses dynamic risk factors to mitigate risk. This may or may not include psychiatric hospitalization. Understand your state law and/or consult with risk management to know how your legal duty is or is not defined in your state.

Scenario #2: You are asked to evaluate a 40-year-old man with a history of schizophrenia, multiple substance use disorders (crack cocaine, PCP, marijuana), and numerous past incarcerations who was brought to the emergency department after he flagged down an ambulance and reported suicidal and homicidal ideations. During the interview, he is uncooperative and increasingly agitated. He endorses command auditory hallucinations to harm others, but he does not appear to be responding to hallucinatory stimuli during your assessment. He also expresses vague paranoia that a peer at his homeless shelter is trying to harm him “because [the peer] is a killer.” He initially states that he wants to attack the peer to protect himself, but later denies this. He subsequently refuses to answer additional interview questions.

- You should be familiar with professional ethical guidelines and duty to warn/protect laws in your specific jurisdiction. As in the first example, you should conduct a violence risk assessment and document this.

- Even if a patient’s threats are driven by an antisocial motive or substance intoxication, this does not change your Tarasoff obligations if you have established a patient-therapist/psychiatrist relationship.

- If you are unsure if the violence risk is modifiable, erring on the side of caution is best practice. This patient likely would benefit from hospitalization given his level of agitation and potential intoxication. Hospitalization would allow for re-assessment of his violence risk as intoxication clears and to observe him for any signs of psychosis.

- If he no longer presents an elevated risk of violence and is not threatening others at time of hospital discharge, you may have fulfilled your duty to protect and may no longer need to warn third parties, since they are no longer at imminent risk. However, you should consult with risk management/institutional policies to clarify your obligation.

- Evaluate the likely consequences of each available treatment option and develop a reasonable risk management plan based on what is clinically appropriate. You should focus on clinical interventions to protect potential victims that also have the greatest likelihood of safeguarding the interests of the patient (ex. privacy and autonomy); unless mandated by state law.

- When you do have to disclose a patient’s threats to third parties, try to involve the patient in the decision if possible. This will likely decrease negative effects on the therapeutic relationship. However, you must also consider whether involving the patient would further increase risk of harm to the potential victim and/or to yourself.

ADDITIONAL TIPS

- Consider use of structured professional judgment risk assessment tools to improve violence prediction. For instance, look up the HCR-20 rating sheet here.

- Consult with a supervisor, legal counsel, and/or your malpractice insurance carrier in difficult cases.

- If you need to warn a potential victim and/or notify law enforcement, limit disclosure to only the minimum necessary information relevant to the threat.

- Be mindful of specific situations, such as cases of intimate partner violence, where providing a warning may be insufficient to fulfill your duty to protect third parties, and may actually exacerbate the danger to the victim by further enraging the patient.

Documentation Tips

- Carefully document your violence risk assessment, including the specific threat communicated by patient, identity of potential victims, and collateral information sources.

- Clearly document that you reviewed and obtained relevant records. When possible, use direct quotes from the patient and collateral contacts.

- Document your decision-making, rationale for the risk management plan, and steps taken to protect potential victims.

- Identify anyone you consult with and document these discussions.

- Document any attempts you make to notify police or third parties and your rationale. Thoroughly document the content of the information you provided to each individual.

REFERENCES

- Anfang SA, Applebaum, PS. Twenty Years after Tarasoff: Reviewing the Duty to Protect. Harvard Rev Psychiatry. 1996 July/Aug;4(2):67-76.

- Cause of Loss – Claims and Lawsuits, 1986-2019 [Internet]. Professional Risk Management Services, Inc. 2020. Available from: https://www.prms.com/media/2439/cause-of-loss-2019.pdf

- Mental Health Professionals’ Duty to Warn [Internet]. National Conference of State Legislatures; 2022 Mar 16. Available from: https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/mental-health-professionals-duty-to-warn.aspx

- Rodriguez L. Message to Our Nation’s Health Care Providers. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2013 Jan 15. Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ocr/office/lettertonationhcp.pdf

Additional Reading

- Michaelson K. Duties to Third Parties. In: Wasser T. Psychiatry and the Law, Basic Principles. Switzerland: Springer; 2017. 35-51.

- Duty to Warn, Duty to Protect, and Duty to Control: The Exceptions to Mental Health Provider Patient Confidentiality [Internet]. SMI Adviser. 2020 Feb 18. Available from: https://smiadviser.org/knowledge_post/duty-to-warn-duty-to-protect-and-duty-to-control-the-exceptions-to-mental-health-provider-patient-confidentiality