Overview | Clinical Scenarios | Additional Tips | References

By Dr. Michael O. Mensah

OVERVIEW

Definitions

(From: Beyond Beds The Vital Role of a Full Continuum of Psychiatric Care):

| Crisis Model Component | Model Definition |

| 988 (via Text, Telephone or Chat) | A 24-Hour Crisis Line that allows for screening, assessment, preliminary counseling, and resources for referrals for mental health or substance use services and suicide prevention pathways |

| Mobile Crisis Teams | Behavioral health professionals who navigate within a region and at the scene of a crisis |

| Crisis Intervention Teams (CIT) | Specially trained law enforcement officers linked to behavioral health designated crisis drop off points of access to care. |

| Co-Response Teams | Behavioral health professionals and law enforcement teams working together to respond to emergency calls for emotional disturbances in the community. |

| Crisis Hubs/Crisis Centers/Coordinated Community Crisis Response Center |

Locations and systems that provide immediate in-person attention to any level of urgent to emergent need for mental health and substance use disorders and may include call centers, drop-in, and drop off sites. |

| Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics (CCBHCs) | Medicaid financed centers that emphasize crisis care and wraparound coordination of care. They provide comprehensive mental health and substance abuse services. |

| Crisis Residential Services |

Services where individuals in crisis can voluntarily reside for brief periods (usually up to 14 days) and receive behavioral health supports in a less intensive setting than inpatient level of care. |

Jurisdictional Considerations

Policy regarding police-psychiatrist interaction varies considerably between cities, counties, states, and regions. However, all interaction will occur against the backdrop of an inadequately resourced mental health care system that often positions police officers to manage patients with decompensated mental illness. Indeed, a survey of over 350 sheriffs’ offices and police departments reported 10% of law enforcement budgets and 21% of total law enforcement staff time was spent responding to and transporting people with mental illness. Over a 10-year period, 28 percent of state mental health service consumers were arrested at least once. 7% of all police contacts involved mentally ill persons.

Efforts to improve this system are in municipalities as varied as Pima County in Arizona, Iowa, New York, and Eugene, Oregon. More broadly, over 42 states have implemented Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics after the success of an 8 state Medicaid demonstration project in Minnesota, Missouri, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Oklahoma, Oregon and Pennsylvania that reduced emergency room utilization and increased access to medication assisted therapies. The implementation of the national 988 hotline and funding from the Biden Administration will facilitate increased growth in services over the next decade.

CLINICAL SCENARIOS

Scenario #1: You’re a third-year resident moonlighting regularly. Your pager goes off Wednesday after clinic; your sickest patient wants to talk. After 10 minutes on the phone, you are more worried: the patient is a Black man with decompensated paranoia, delusions, and disorganization indicating psychosis, and he thinks the police are after him.

Scenarios like these occur regularly. Approaches at your disposal will vary depending on where you practice.

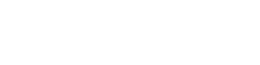

- The most common service is law enforcement crisis response with limited training (average: less than 21 hours) (Figure 1).

- Non-police options are increasing, but not the norm currently.

- When calling for help, be sure to inform the dispatcher of your patient’s paranoia, especially if ideations involve police.

Figure 1: Examples of Crisis Services (taken from Beyond Beds)

Components of mental health crisis response (described in Definitions) will vary even within these 4 categories.

988, the new mental crisis hotline launched in July 2022, aims to provide more appropriate mental health crisis response (Figure 2, taken from Crisis Services Meeting Needs, Saving Lives)

More Tips

- If you are concerned about your patient’s safety, please call 988 for a safety check.

- You can also call the police station nearest to your patient’s residence and ask for a safety check, but this is an indirect means and may take longer

- If there exists only a default law enforcement crisis response in your area, your patient may be at greater risk of being injured in the presence of police, especially if they have a serious mental illness (10.7 times the risk [95% CI, 9.6–11.8]), or appear to be a racial or ethnic minority. In addition, exposure to police increases the likelihood of future psychotic experiences.

- In these cases, inform the police of the patient’s mental illness and current state as best as you might ascertain, since they may have personnel who are trained for such situations.

- Patients have taken legal action after a safety check has gone wrong, alleging violation of their constitutional rights.

Documentation

- Be sure to document safety plan for high risk patients, including advising them of emergency resources

- Explicitly note your thought process that led to calling for a safety check.

- Note other steps taken (e.g. reaching out to patient, asking about medication) to ensure patient safety.

Further Reading

- Decoupling Crisis Response from Policing — A Step Toward Equitable Psychiatric Emergency Services

- Crisis Services Meeting Needs, Saving Lives

Scenario #2: 32-year-old male with a history of schizoaffective disorder, methamphetamine use, and a recent stay in jail presents to the Emergency Room brought in by police after being found shouting to himself in the middle of the street. His labs are normal except his urine toxicology, which was positive for methamphetamine. The officer who brought him to the ER wants to get his urine toxicology results. What should you do?

- There are guidelines to help with this scenario. You should consider state and local law and both the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) as well as 42 CFR Part 2, which concerns the confidentiality of patient information regarding drug and alcohol use and is more restrictive for its “federally assisted programs”, which usually include centers providing addiction care financed by Medicaid.

- Police officers do not provide care, and are generally not bound by HIPAA or 42 CFR Part 2. This means that if they learn protected health information about any person, they are free to disseminate that information as they choose.

- In contrast, if they received the information through a court order—like a warrant—they would need to respect patient privacy.

- HIPAA permits disclosure of certain patient data (described below) to identify or locate a fugitive, missing person, suspect, or witness

- Name and address

- Date and place of birth

- Social security number

- ABO blood type and Rh factor

- Type of injury

- Date and time of treatment

- Date and time of death, if applicable

- A description of distinguishing physical characteristics:

- Height

- Weight

- Gender

- Race

- Hair and eye color

- Presence or absence of facial hair (beard or moustache)

- Scars and tattoos

- HIPAA does allow PHI transmission to a police officer if a health provider or hospital entity believes such disclosure is required to prevent or lessen a serious and imminent threat to the health or safety of a person or the public and if the disclosure is to someone who can prevent or lessen the threat.

- Consult with in-house legal/risk management since jurisdictional differences do occur

- Please see HIPAA & Statutory Regulation Section for more discussion

ADDITIONAL TIPS

- You should not give the officer the information without a warrant, unless state or local law allows, or you think the officer is in position to reduce an imminent threat using this information.

- Hospitals may not disclose any protected health information related to DNA or DNA analysis, dental records, or typing, samples, or analysis of body fluids or tissue.

- You can choose to disclose certain protected health information in response to a law enforcement official’s request for “the purpose of locating or identifying a suspect, fugitive, material witness, or missing person,” as stated above, but the officer is not reasonably positioned to reduce a threat. As such, you are not mandated to turn over this information. Involuntary tests administered under these circumstances have been determined to be inadmissible evidence in court.

Documentation

- If you decide to give police information, document clearly the source of information that compelled you to do so.

- Document the police officer’s name and badge number.

- Explicitly state the criteria that led you to give information

- Did the officer have a warrant for the information?

- If so, document, and even consider taking a picture of the warrant to put into the electronic health record.

- If not, was the patient a suspect, fugitive, material witness, or missing person?

- If so, record how you know this.

- If not, strongly consider whether or not to give patient information to the officer.

- Obtain a consultation from your hospital’s legal team, record that you did so, and that they concur with your decision.

- Did the officer have a warrant for the information?